AI Versus Beethoven

I just checked with ChatGPT to see what it “knows” about Musimorphic (TM). Zip. Zero. Nada. Same goes for Grammarly, by the way. Of course, the ChatGPT free version stopped “learning” in 2022, so there’s that.

This is the same ChatGPT that believes Classical favorites such as Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” and Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” are in the key of C (they’re in A minor). It also mistakes Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” from his Ninth Symphony as being in C when it’s in D.

Doesn’t this illustrate a very big gaping hole in generalized AI?

I can see two halves in this hole, which I’ll state here as assertions:

- AI is focused on what gets the most attention;

- AI’s attention-based focus can cause it to make dumb mistakes.

The Worlds She Sees

Dr Fei-Fei Li, in her book “The Worlds I See – Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI,” gives us a mid-2023 perspective on how AI came to be and what it must consume to become artificially “intelligent.” To put it simply, a growing AI needs to learn…everything. And, even at that, everything is never really enough for any given AI to be fail-safe.

Dr Fei-Fei Li, in her book “The Worlds I See – Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI,” gives us a mid-2023 perspective on how AI came to be and what it must consume to become artificially “intelligent.” To put it simply, a growing AI needs to learn…everything. And, even at that, everything is never really enough for any given AI to be fail-safe.

In that regard, I agree with the good Doctor.

She also makes the observation that, although AI algorithms are constructed by the best and brightest technology-savvy humans available, there are aspects of AI that no one understands, whether in its success or in its failure, and, that no amount of computational or financial resources as yet seem to be able to better that understanding. As honest as it is, that sounds goodly and promising, too.

I have no trouble with the use of AI to offer medical advice or advances that can be confirmed using non-artificial means. Same for any other limit-pushing opportunity. There is, however, one major area where actual human beings ought to disagree vehemently with AI: its ability to learn the truth.

Let us take a simple example.

Ludwig: Can You Hear Me?

How many copies of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” do you suppose are available online right now, ready for your (or your kids’) budding musical talents, to purchase, learn, and perform? Probably quite a few. Out of those, how many do you think are in the key old Ludwig actually used to compose his Ninth Symphony? Generally, orchestral scores would be in the originally composed key, as opposed to arrangements or reductions, or simplified versions intended to be easier to play for amateur or novice musicians, and you don’t take my word for it: the whole score is available from the Library of Congress for your independent research.

More to our point, let’s ask the Oracle. A quick search for “Original+Score+Beethoven+Ninth+Symphony” returns about 10 million results. A search for “beethoven+ninth+symphony+easy” has 890,00 results. That seems counter-intuitive, doesn’t it? Especially since AI gets the key signature of the Ode to Joy wrong when the number of “correct” online instances of it far outweighs the “easy” versions, many of which are in the key of C?

What if the easier versions of the Ode to Joy simply attract more attention, particularly from people who want to learn to play it, than do the “correct” ones? Hang on to that suggestion for a moment and let’s see how it plays in the Peoria version of AI.

Dr Li Again

First, a bit more about “The Worlds I See.” (You’ll need this understanding to get to the end of this article successfully.)

Dr Li points out that training an AI is limited in many ways, ranging from the availability of the source learning materials to the computational speed at which any given AI can absorb information. This means that the human beings responsible for putting reasonable boundaries around an AI learning project must make some choices – choices that, as Dr Li points out, are often limited by physical and financial constraints.

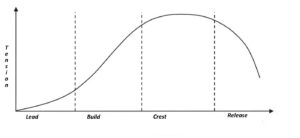

To make any kind of progress in our current era – which could change tomorrow – AI must be focused on the information that is most “active” and tends to ignore or downgrade information that is not quite so active. To The Algorithm, activity is an indication of credibility. In other words, the more times an easy version of Ode to Joy is accessed, the higher the probability that this is meaningful in some way to a nascent AI.

The results? Even when an online preponderance of presence is easy to ascertain (as we did in our searches just above), presence means nothing when popularity is in play. Why? Because machines can use perceptions of popularity – likes, clicks, downloads, comments, and other such activities – as useful boundaries of their machine learning. Too bad that this can result in obvious mistakes that could easily be corrected.

“But that would never happen in a “real” AI!” I hear you say. You may be right, although I suspect Dr Li is better qualified to speak to the accuracy of any given AI than I might be. She has, after all, been there since the very first visual AI began its learning, and some of those AI learning skills could probably apply to the measurement of the pitches in any piece of music just as easily as they could apply to image recognition. So, I hear you say, as much as there’s a lot of learning left to do around “the” tonality of an entire symphony, even when the actual title of the work includes something obvious such as “Symphony blah blah blah in C Major,” what does it really matter? Just because a composer named their symphony in that obvious way doesn’t mean they symphony will stay in that key the entire time, right? So what’s your point, Bill? It’s not like there are lives on the line.

So what does the actual correct key of a symphony (or of “Stairway to Heaven”) have to do with using AI for medical research? Glad you asked. Let’s take a mental trip back in time a few years and explore some possible answers.

That Pandemic Thing

Remember The Pandemic? Early on, machine learning – possibly even AI – was brought into play in research to find a vaccine for the Big C that ailed the world. One shining example of this was the University of San Francisco, and its research results helped re-purpose existing medications to aid those suffering. It was solid research. It was also mostly ignored and/or deprecated by the Powers That Be. This set up a tension that produced a huge volume of likes, clicks, downloads, comments, and other such activity across the entire Internet worldwide, as well as heated debates about what information was factual and what information was not.

Now, if you’re a learning AI coming up to speed on the COVID–19 infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, what are the boundaries of your learning? If studies from research are on your radar (as we hope they are) then the results of scientific research, even if inconclusive, surely ought to inform you. What about the infinite volume of conspiracy theories, government mandates, and popular opinions available online? Do you choose to deprecate that based on some criteria or another, or do you consider it in some way in the process of growing your knowledge? Do you take into account that actual human beings as well as social media algorithms were actively and arbitrarily hiding some of the knowledge?

Also early on, human experiential learning (and maybe some luck) in a clinic in the middle of nowhere discovered that symptoms of COVID could be treated rather successfully. Their on-the-job experience was deprecated by powerful government entities. As a learning, AI, what do you do with that information? As a researcher, do you “trust” this new AI to give you all the necessary facts, even with the understanding that some of those facts may be either bogus or assailable by others for their own reasons? The treatment proposed by these honest hard-working clinicians never saw the light of day, and it may have saved many lives.

AI Versus Everyone

Isn’t the point here that machine learning could potentially find itself at odds with popular culture? Just as with the key signature of Ode to Joy, our current AI learning capabilities are in fact limited, and we must impose some arbitrary limits on the learning activity for capacity and cost reasons. How are those choices made, especially when they involve world health, economy, or governance?

If we permit an AI to learn in a popularity-centric environment, we deserve the results we get from such an AI. Until and unless we can achieve true artificial general intelligence, asking AI for the key signatures of well-known music may simply just be unreliable. Still, due to the unknowns Dr Li observes, the simple acquisition of knowledge alone may not be enough to guarantee in any useful way that AI is or can ever become infallible.

And that ought to concern every one of us, from marketers and administrative assistants with their “AI chatbots” to the powerful actors, good or bad, capable of co-opting large swaths of influenceable human beings. So long as there is the possibility of AI getting it wrong, human discernment – even informed by AI – ought to continue to have the last word.

_____________________________

Over the course of more than 40 years of paying attention to how music works on us, Bill Protzmann has rediscovered the fundamental nature and purpose of music and accumulated a vast awareness of anthropology and sociology, as well as the effects of music, the arts, and information technology on human beings. Bill has experimented with what he has learned through performing concerts, giving lectures, facilitating workshops, and teaching classes. He first published on the powerful extensibility of music into the business realm in 2006 (here and abstract here). Ten years later, in 2016, he consolidated his work into the Musimorphic Quest. In this guided, gamified, experiential environment, participants discover and remember their innate connection to this ancient transformative technology. Also, The National Council for Behavioral Healthcare recognized Bill in 2014 with an Inspiring Hope award for Artistic Expression, the industry equivalent of winning an Oscar.

Musimorphic programs support wellness for businesses, NPOs and at-risk populations, and individuals.