Solfeggio Tones Explainer Video

A Fun List of Songs in 528Hz – The Love Frequency

Solfeggio Tones Harmonics

With rudimentary maths, one may calculate the harmonics of any fundamental frequency or derive a fundamental frequency for which a given frequency is a harmonic. ChatGPT comes in handy for this, and the link given here offers some insight into whether or not the Solfeggio Tones are in any way related to harmonics of tones that occur organically, such as the Schumann Resonance (7.8Hz – audible to humans at its fourth harmonic, around 31Hz or B0 on the piano keyboard) or tones one might hear in nature or music.

In short, only three of the nine Solfeggio Tones are related mathematically (harmonically) to what we might call “musical” tones that occur organically. The other six frequencies are, as ChatGPT points out, harmonics “of a more complex waveform with multiple frequencies” (this is explained in the last question in the chat).

ChatGPT on Solfeggio Tones and Harmonics

Solfeggio Tones Notation

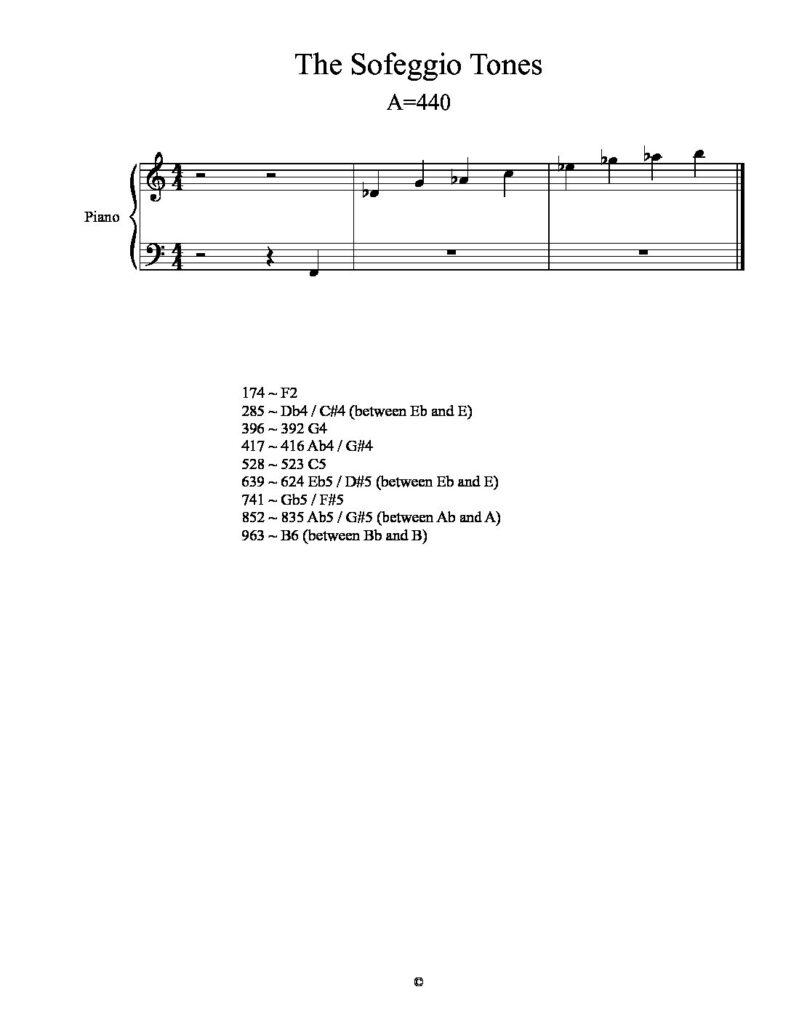

The Solfeggio Tones – Score (click the link or pic to download) shows the Solfeggio Tones in relationship to A=440 tuning. Remember: the Hz (frequencies) of the Solfeggio Tones themselves do not change!

There’s a chart further down this page called A Quick Summary that shows how the Tones align to A=432Hz too: five of the Tones align closely with A=440Hz tuning, while only four align closely with A=432Hz tuning.

___________________________________________________________

Explore pure tones of any frequency with this Online Tone Generator…

…or generate more than one pure tone at a time to make your own binaural beats with this Multiple Tone Generator.

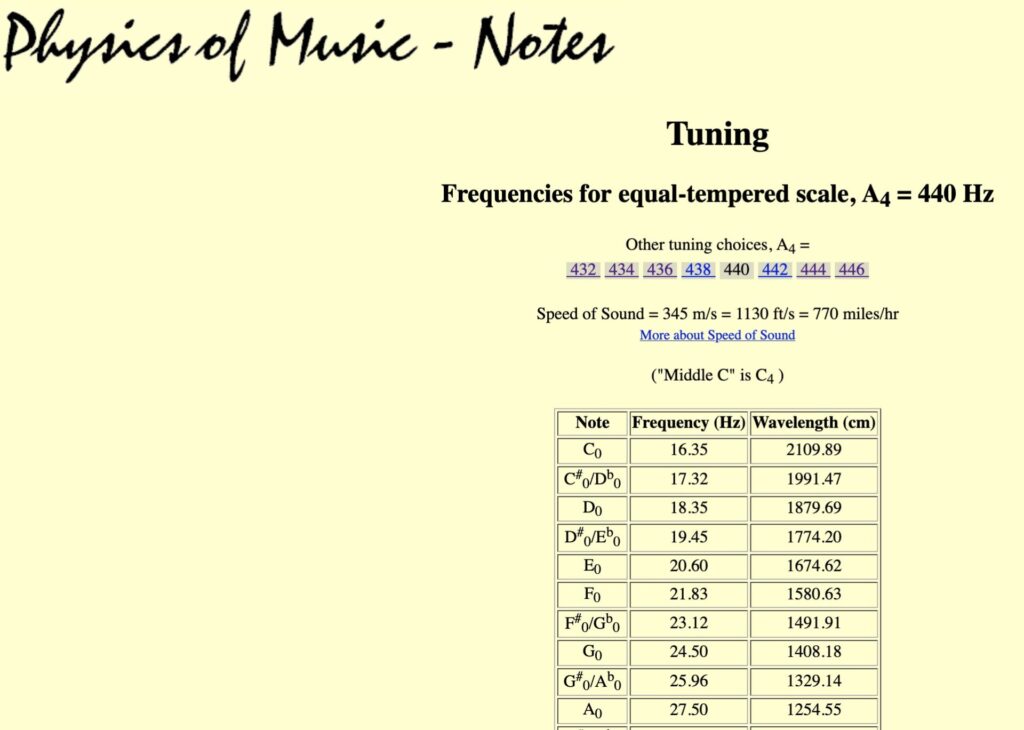

An interactive table of equal-temperament pitches by frequency (Hz) for A4 at any of eight selectable Hz: 432, 434, 438, 440, 442, 444, and 446 Hz:

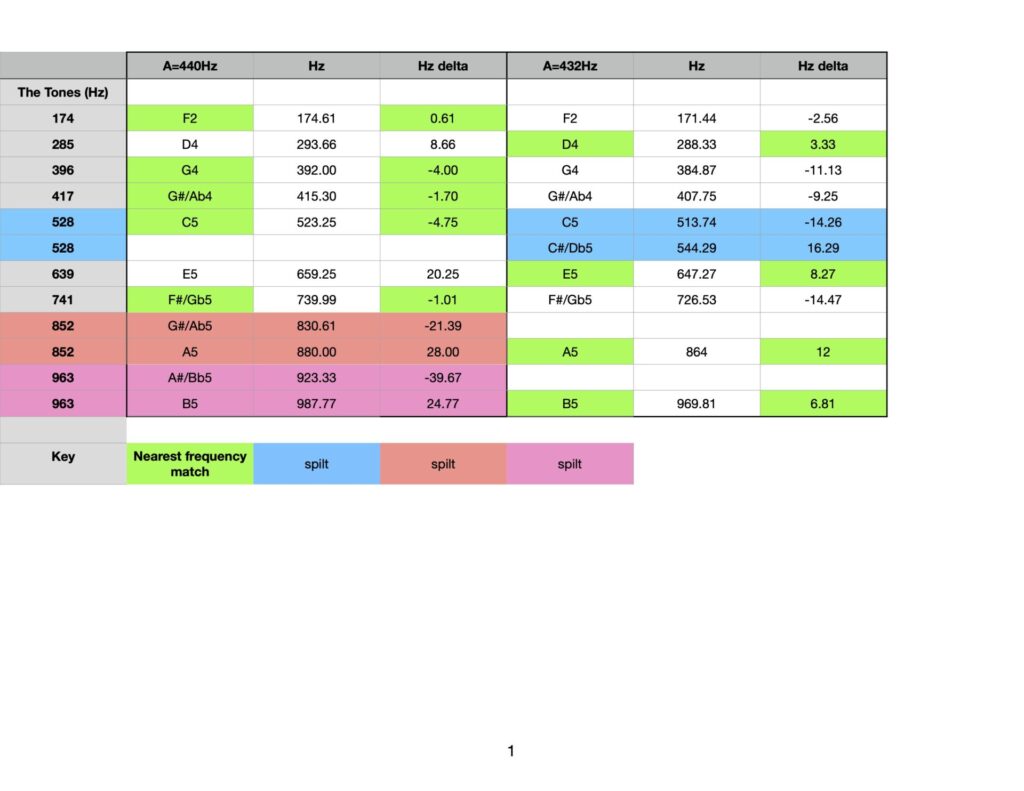

A Quick Summary

Here is how the tones relate to A=440 and A=432 reference tuning – the green bars indicate the nearest frequency match in each of the two tuning reference pitches.

Three of the tones – 528Hz, 852Hz, and 963Hz – split the difference between common (Western) intervals as indicated in blue, salmon, and pink.

Click for a PDF download.

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________