There is a grand effort being made these days to advance “sound healing” in ways that have little to do with how human beings actually respond to sounds, timbre, rhythm, and melody – “music” as it is commonly called, or “music healing” such as advanced by the profession of music therapy and other music healers. This document offers information and insight about the difference between mono-frequency sound healing and other uses of music for healing and wellness.

To be responsible, we must acknowledge that sound, timbre, and rhythm are powerful, and that the choice to use them for good or for ill has always existed. We will focus here on their beneficial effects.

Mono-Frequency Modalities

The proponents of mono-frequency modalities – Solfeggio tones being a prime example, or the debate over whether to tune concert A to 440Hz or 432Hz, or cymatics – miss the actual importance of the power of even a single tone. Here’s why.

To the unaware, mono-frequency healing can seem quite scientific, in spite of the lack of true scientific evidence for its claims. The root assumption underlying mono-frequency modalities is that the human body will enter a state of wellness if and only if it resonates with a particular and very specific frequency, measured in cycles per second or “Hertz.”

Other than the fact that true mono-frequencies could only be produced by electronic equipment beginning in the early 20th Century, mono-frequency modalities claim “ancient” origins for their specific frequencies, conveniently ignoring the fact that an organic tone is not pure – that is, confined to one and only one number of cycles per second (Hz) – because sounds made organically always contain overtones (harmonics) that are mathematically predictable. Therefore, a mono-frequency is not a single frequency at all, but a fundamental tone accompanied by the fifteen or sixteen harmonic intervals that fall within the range of human hearing, as well as a theoretical number of harmonics which cannot be heard by the human ear but can resonate within the human system. Thus, mono-frequency modalities posit that human wellness is grounded to a fundamental tone with a specific number of Hz (the Hz value changes based on the attributes of wellness desired) and its harmonic overtones.

While there is no scientific evidence that attuning a human body to a specific Hz and its corresponding harmonics is in any way beneficial, belief and anecdotal evidence are contributing factors in support mono-frequency healing claims. Doubtless many psychosomatic illnesses have been “cured” through the combination of belief and unsupported pseudo-scientific claims, and if health and wellness are restored, that’s a good thing. There is, however, a significant gap between the basic science of mono-frequencies (because they aren’t) and the assumptions underlying what is claimed for them.

To the contrary, the scientific evidence that does exist for pure-Hz mono-frequencies has been explored via the destruction of organic tissue at Hz in the range of what we would call “ultrasonic.” These ultra-high frequencies have been successfully used to destroy leukemia cells in the human body and, one assumes, this is done with equipment that can produce a pure tone at a specific frequency without its accompanying harmonic overtones. There is as yet no evidence that sympathetic vibration of body tissue or internal fluids offer measurable harmonics when a single-Hz frequency is “played” with the intention of destroying cancerous tissue. For more on this, visit the following CalTech website for February 4 2020 news item: https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/ultrasound-can-selectively-kill-cancer-cells

Chanting, Toning, Drumming

Monks have sung the “OM” for thousands of years, and First Peoples have used drums for just as long, all with shamanic intent. Tuvan throat singers demonstrate the ancient art of multi-frequency toning (blending audible harmonics in a single human voice). Do these modalities heal? In truth, they are able to do much more than that. Musicologist and author Ted Gioia’s book, “Music to Raise the Dead,” which is being released on Substack one chapter each month, provides evidence that the use of such music (for we have now graduated from mono-frequencies to a more structured production of sound, timbre, and rhythm), has been used for magical purposes since before antiquity. https://tedgioia.substack.com/p/music-to-raise-the-dead-the-secret

The first thing to note about these practices is that they are often communal – many instruments or voices participating in an immersive experience. Unlike the healer/patient relationship, chanting, toning and drumming can extend to a group. Member of the group participate in the magic together, each with their own instrument. Non-performing “witnesses” to such a “performance” also benefit – which was the intent – by attuning with or vibrating in sympathy with the music being made. Ritual was often a component of the experience, usually guided by a shaman, and, from what is known about such “concerts,” a through-line story could be included, usually a story of deep historical or spiritual significance to those in attendance.

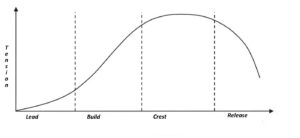

These “first musics” grounded entire indigenous cultures around a shared wellness. The motion and variations of tension in such experiences combined with the music to awaken and remind participants of the importance of their shared heritage while inviting a trance-like state of awareness and wholeness to the entire group. While the nature of the experience varied from the stillness of the OM to the sacred exuberance of a pow-wow, their shared purpose was healing, connection to the Other, and the strengthening of the community, especially when used to invite protection, forgiveness, or even conflict when it was necessary.

For completeness, the production of sounds organically in these types of modalities always included (and includes) the harmonic overtones associated with the human voice and the drum. Into this range of frequencies, one can imagine the deep resonance of the largest Taiko drum, the mid-range multi-frequencies of the metal singing bowls and the human voice, rudimentary plucked, bowed, whistles, flutes, or blown-reed instruments, and ceremonial bells and gongs. None of these devices would have been capable of a pure-Hz frequency; all would have offered harmonic richness and some, particularly those capable of audible harmonics, would have produced what are now called “binaural beats.”

Binaural Beats

Modern scientific measurement of sound lets us accomplish tasks such as tuning a guitar with relative ease. Before electronic tuners were available, however, tuning a guitar, piano, harp, or other stringed instrument was done “by ear,” a skill that all string players must master. For large groups of performers, some agreement about a fixed reference pitch was needed, such that instruments could be consistently tuned and perform harmoniously together. For string, woodwind, and horn players, tuning to the reference pitch was de riguer and easily accomplished. For other instruments, such as tuned bells, pipe organs, and complex harps, tuning up just prior to performance was either a lengthy process (in the case of a harpsichord, pipe organ, or piano) or impossible (in the case of tuned bells).

When two tones are produced that we experience as “out of tune” there is a physical measurement of their out-of-tune-ness that can sometime be heard as a wobble in between the two pitches. The most obvious case, for anyone who has happened to fly in a dual-engine propeller-driven aircraft, can be heard when the Hz produced by the left-hand motor’s propeller is slightly out of sync with the Hz produced by the one on the right-hand side. Skilled pilots know how to “tune” both engines to be harmonically in sync, the same way that a piano tuner used to tune two or three strings for a given pitch “by ear:” they listen for the wobble (or beat) and make fine adjustments until the wobble disappears.

The wobble between two slightly out-of-tune pitches can itself be measured in vibrations per second, or Hertz. Let’s say, for example, that we decide to tune to a reference pitch of A=432Hz. Most commonly, instruments are set up for A=440Hz, so the various players in our little band would spend a few moments tuning to the new reference pitch, during which time we might hear (if we were allowed to sit in) some wobble between the instruments as they tune up. The measurement of that wobble in Hz is the mathematical difference between the reference pitch of A=432Hz and A=440Hz, or 8Hz. There’s not an 8Hz tone, mind you, it’s an 8Hz interference pattern between the two reference pitches that we experience as the band corrects to the new reference pitch.

If one were to simultaneously play a pure 432Hz tone (no harmonics) and a pure 440Hz tone, the 8Hz wobble would be obvious. Fortunately it is easy to do this little experiment using tools such as the Online Tone Generator, available here: https://onlinetonegenerator.com/

This measurable wobble between two frequencies (Hz) has been called in modern times a “binaural beat,” and in the experiment above, we would describe what was heard as an “8Hz binaural beat.” It is important to note that, while we experience the wobble or beat, we don’t actually hear it, since the experience is one of absence of sound (the physics aren’t necessary to understand but they can easily be found online) where the peaks and valleys of 440Hz and 432Hz cancel each other out eight (8) times per second (the Hz of the beat itself). What we hear are the two tones (432Hz and 440Hz simultaneously) with a wobble (the 8Hz binaural beat).

There are, of course, binaural beats that fall both below and above the range of human hearing. The harmonics we have discussed are one such example and, while the physics of harmonics are fascinating, they are beyond the scope of this essay. The important point to recall is that, while me way not be able to perceive each and every binaural beat, the probability of them taking place organically, even in the simplest music, far outweighs the probability of every instrument or voice being precisely in tune with every other at every instant during their music-making. Generally, this means that the frequency of the beats is small, as in our 8Hz example above, although it could be as wide as the entire range of human hearing (20Hz – 20,000Hz) or wider – remember that we don’t actually hear binaural beats, we experience them as the Hz difference between two pitches).

It has been suggested that, as with mono-frequencies, binaural beats can influence the Hz of one’s body, particularly, the brain, which itself vibrates at well-known frequencies that correspond to the work the brain is actually doing, and that using binaural beats in this way can entrain the brain (and body) to a desired state, from down-regulated deep sleep to up-regulated active wakefulness. Clearly, since tuning instruments has been mostly an imprecise endeavor for many thousands of years, human brains and bodies have experienced the “beats” of slight out-of-tune-ness for the same amount of time, and it is only in more modern times that slight differences between tuning have captured the imaginations of those with an interest in their potential power for entrainment.

We can say with some conviction that binaural beats have been with us since two or more instruments or voices first sounded together, as well as in the case of multi-harmonic instruments such as singing bowls or bells, were produced by a single “tone generator,” and that binaural beats have therefore been a part of communal music-making for the same period of time, but actual scientific inquiry into the wellness and health claims for them has yet to be taken seriously. “Sound healers” embrace binaural beats and use them often, especially since a wide range of beats can be generated with modern tools, and while there is no doubt that binaural beats have various effects on the human brain and body, these effects often vary widely and can be quite specific and personal to any random person who experiences them.

Cymatics

We are now at a point in our discussion where the observable effects of frequencies become visible. That is, while vibration, say, of a guitar string is often imperceptible to the human eye, modern technology can reproduce those vibrations using laser light or, more fundamentally, with solid particles resting on a co-resonant sound board, such as the back of guitar or the sound board of a grand piano. Just as the wobble between frequencies has been dubbed “binaural beats,” the modern observation of particulate response to pure-tone frequencies is now called “cymatics.”

When the harpsichord was invented, for example, musicians delighted in sprinkling charcoal, sand, or rice on the sound board and striking the same note repeatedly to observe the patterns made as the particles on the sound board arranged themselves symmetrically into patterns. As one might expect, different notes produced different patterns. This experiment has been reproduced using various resonating surfaces and with pure-tone generators (one Hz no harmonics) which create very specific ad elegant patterns which are somewhat dependent on the particulate matter used. There’s an almost infinite variety of such experiments available online.

Leaving aside the analogous experiments in which ice crystals form coherent patterns under the influence of directed “good” intentions while forming dis-coherent patterns under the influence of chaotic or hurtful intent, there is a school of thought that claims that beautiful patterns can emerge in the human body under the influence of specific pure-tone frequencies. Once again, we are back to mono-frequency thinking! The difference between cymatics and, say, Solfeggio tones, is that cymatic frequencies are pure-Hertz tones rather than tones with overtones, as would have happened in the “ancient” practice of Solfeggio.

Cymatics has been postulated to extend to sound levitation (many examples online) and as been suggested as a possible way to move very heavy objects (were the pyramids of Egypt built using cymatic transportation?) as well as sound sculpting (were the precise dimensions of many thousands of identical blocks in the pyramids “carved” cymatically?). Much work remains to be done to substantiate such claims, especially since the types of tools required to levitate even a small rock may not have been technologically possible in antiquity, but cymatics will doubtless offer plausible theories to explain the currently unexplainable.

Where cymatics and healing intersect seems most plausible here: at the level of single-cell destruction, such as posited by CalTech in the article cited above. One cannot discount the net-positive healing or wellness effects of cymatics as it may exist in a pure-tone subset of the mono-frequency practices, but doing so would be a refinement over the traditional mono-frequency practices, since pure-tone frequencies are a relatively modern evolution of sound that have existed during thousands of years of harmonic-rich organic music.

The Human Resonator

I’m not a biologist, physicist, or neuroscientist. However, as a musician who’s interested in the physical effects of music, it is nice to have easy access to the latest research on music’s capabilities relative to the human system. There seems to be agreement in scientific circles that our human systems do in fact respond to vibration, and, at least in the neurosciences, this response has been used extensively to measure the brain’s response to musical stimuli and from those studies to suggest theories about how the brain and body respond to given kinds of sounds. Plenty of literature on this topic exists, and much of modern music therapy is guided by neuroscience and repeatable experience in this area.

With the exception of the research being done by the Heart Math Institute, much of the musical response consistently measured by modern science fails to consider human emotions and, more importantly, what might be called the musical effect on one’s “spiritual self” or “higher consciousness.” Consciousness and “energy” research does exist, and to the extent that one believes that “consciousness” resides somewhere in the brain, the research may be compelling, but the most ancient music we know was not interested in particulate manipulation, brain waves, or mono-frequency response, was it? If we recall the original purpose of music, it was much more magical than the measurements science offers us today.

Human beings naturally resonate for vibration, yes, and human beings also have a built-in desire for something more. Imagine yourself at a mono-frequency concert, for example, where the tone A=432Hz was performed for 45 minutes. Would you be bored? Or pick any of the other popular tones, such as the Solfeggio “frequencies” (they aren’t pure frequencies, so this is a nod to their proponents for effect): could you sit still for 45 minutes of a single pitch? This is preposterous, of course, but it is analogous to attending a movie where one character sits in a chair for 90 minutes doing nothing except starting back at you in the audience. Even the famous (infamous?) “4 Minutes 33 Seconds” piece is meant to remind us of the organic nature of ourselves, the concert hall, the intention of the performer, the ambient sounds around us, and the thoughts and feelings we have inside us as the piece is performed. In short, we need something more.

That something more comes when music and story coincide. Even the simplest melody tells a story, and shamans have used the movement of frequency for this simple reason: we must be enchanted with the music in order to experience its magical effects. Variations in rhythm are familiar to drummers, and we in the audience respond organically with movement and entrainment of our physical selves, which can lead to trance states of higher consciousness. Human beings crave this entrancement, and we offer the entertainment industry rich rewards for providing it to us.

On the other hand, modern sound healing has no such rewards. It seems to be both a scientific and logical step backwards to offer mono-frequency modalities into a world so rich in music rather than embracing the potential for sound and rhythm and advancing its capabilities in ways that people actually find useful and supportive of their wellness. On balance, however, one could admit that the busyness of modern life in our 21st Century demands a kind of counterbalance such as that offered by mono-frequencies, but let us recall that The Age of Enlightenment, from which much of the mono-frequency oeuvre has descended, was quick to discard truly “ancient” and “shamanic” practices in favor of novel ones, and that this same age also gave use the decimation of indigenous peoples worldwide in favor of cultural and religious ideas that overrode much of what we now hope to regain in the name and nature of wellness and health.

Whole Music

The logical and obvious point of this essay is that the human desire for a music that is much more complete, both in terms of harmonic richness and compelling interest, is not served by mono-frequencies or binaural beats in isolation. Instead, the human system – mind, body, and soul – craves a more holistic music: music that has a directed complexity of melody, harmony, timbre, and rhythm, which invites listeners to an experience of wholeness. To fully embrace this kind of music, we mere mortals must un-learn much of what Enlightenment practices have taught us and return to a more primitive and more magical sense of the possibilities available in music. Music Therapy as a profession has done and will do much to bring this notion into evidence-based, practical, clinical connection with those who need it most, and music therapists have been deploying recreational music-making as a tip-of-the-hat to ancient shamanic practice for some time, although they board-certified music therapist wouldn’t say it that way!

As entertaining as musical events can be, you don’t need anyone else to give you a musical healing. Ask yourself: What music do I truly love? As you consider that for yourself, you may begin to notice that the music which has really “gotten into you” has a certain timeless quality about it, that it has an effect on you which is difficult to put into words, and, that when you do find some words to express your connections to the music you love, they feel quite inadequate to the task. You may have memories around the music you love that are an indelible part of your life. Your music may connect you to other people or communities in ways that are also ineffable. Whether your music seems rudimentary or complex matters not; you may have a connection to the sounds of nature or the sounds of a symphony orchestra, or even to certain important naturally-occurring tones (such as the Schumann resonance, which is inaudible, but often mimicked in the audible range in ambient music), or to chant, toning, drumming, or favorite bands of your adolescence, the important consideration around the music you love is how it has impacted you personally. For you, that is what we could call “whole music” because it is in essence the music of your personal wholeness.

Could this music you love also be your healing sound track? Are you ready to explore the depths of healing available in it? Would it be of interest to you to learn how the combination of intention and music in the ancient practices of musical “magic” can be reproduced today, by you, whenever you need them and for whatever purpose you might have? And, a final question, why aren’t you already doing this?

As a healing technology, music is primary. One doesn’t have to wait for neuroscience to explain how the various components of music work on the human system, just as one doesn’t have to wait for a mathematician to explain prime numbers to be able to use any number in basic arithmetic. Mono-frequencies are disadvantaged in the healing work for this same reason; the wholeness of music extends far beyond single notes just as the wholeness of the human system embraces the movement and magic of song, story, tension, release, and an openness to the numinous that can’t be found in the minutiae of measurement. Instead, the invitation to come home to this built-in human technology is a profound one. Are you ready to accept, take the first step on this long-forgotten road to true health and wellness? Your music is calling; how will you answer?

__________________________

Bill Protzmann has advocated for improved consciousness for over thirty years. With an understanding of music, you can build skills such as those discussed here: intuition, intention, and compassion. Learn more about this work and take the online heroic Quest for transformation at Quest.Musimorphic.com